Pastoral Job Description: Shared Church

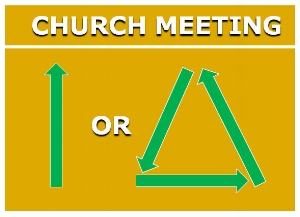

Suppose a church begins acting as an assembly of priests (see previous two blogs). What, then, does a pastor do? Will practicing the priesthood of all believers impair pastoral work? Might the fear of a reduced role discourage pastors from sharing the priesthood? Since the Reformation, Christians have spoken of the priesthood of all believers. Spoken of? Yes. Practiced? Not so much.

Daryl McCarthy, with the Forum of Christian Leaders, says, “Tragically, the priesthood of all believers is the one Reformation doctrine that has never been fully embraced by evangelical churches.” And Dr. Art Lindsley adds, “The priesthood of all believers has been the most neglected central teaching of the Reformation.”

But why?

Might pastoral job descriptions be putting a damper on practicing a shared priesthood?

I just reviewed a few such job descriptions offered as models. They have the pastor doing nearly everything in gathered-church meetings: preaching, leading worship, administering ordinances, and officiating at baptisms, weddings, and funerals. One job description has the pastor heading all boards and committees to develop the vision for the church, supervising staff, providing pastoral care, and so on. The first sentence in one model said: “The pastor is to be the spiritual leader of the church.” Not one of the spiritual leaders, but the spiritual leader.

In most cases, pastors get paid to do what these job descriptions call for. Those in a congregation typically receive no compensation for doing church-related work. So, paychecks add pressure on pastors to carry out their extensive to-do lists. Any surprise so many burn out?

What, I wondered, might a pastoral job description look like if it were written for a church that wanted to actually live out the priesthood of all believers? My pondering prompted me to jot down a list—practices that would connect the dots between how the New Testament pictures church leadership and congregational life in the 21st century. Would the following role description fit every setting? No. But I hope it will stimulate some creative thinking:

Job-Description: Shared-Church Pastor

Job Title: Pastor/Elder

Reports to: Board of Elders and Church Body

Job Summary: The pastor/elder, coequally with fellow-elders, is responsible for watching over and nurturing the life of the church body and for preparing those within it to serve in both the gathered and scattered church.

Primary Job Responsibilities:

Sets an example for other believers by:

- Maintaining a vital relationship with Christ and with others in both the gathered and the scattered church.

- Living a life—in attitudes, actions, and speech—God would approve as a model for other believers in the church body.

Together with fellow-elders, ensures that the gathered church is fed regularly with sound biblical teaching and guards the church against false teaching.

Shares with fellow-elders the work of helping those within the church body to identify and develop their God-given spiritual and natural gifts.

Helps to recognize and train others within the church body who are gifted and motivated to serve as elders, to preach and teach, and to lead the gathered church in public prayer.

Oversees the setup and maintenance of:

- A listing of those in the church body with ministries in these five sectors: family, school, marketplace, neighborhood, and hobbies/recreation.

- A church-wide prayer ministry for those ministering in the five sectors.

Sets aside one day a week to spend “on location” with those in the church body who minister in one or more of the five sectors, gathering their prayer needs and hearing their stories of how they see God working.

Coaches believers in writing and presenting personal testimonies.

Structures gathered-church meetings in such a way that they provide opportunities for:

- Those with teaching gifts to develop and exercise them.

- Those who have been prepared to do so to lead in public prayer.

- Christians to report on what God is doing in their ministry sectors during the week.

- Public prayer for the issues and opportunities Christians are facing in their workplaces, families, neighborhoods, and other areas of their weekday lives.

Invites and helps to prepare others in the church body to baptize believers and to take the lead in overseeing the celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

Seeks to include personal testimonies in gatherings for baptisms, weddings, and memorial services.

Pastoral Role Enhanced

So, practicing the priesthood of all believers in a shared-church context does not set aside or reduce the importance of pastoral service. Rather, the pastoral role becomes even more important as catalyst and multiplier, releasing the gifts and ministries of others.

In our traditional non-practice of the all-believer priesthood, church governance language often says that elders, boards, deacons, etc., “shall assist the pastor.” Shared-church practice turns that upside down. Pastors/elders assist other priests to develop and carry out their respective ministries in the gathered and scattered church. In doing so, they fulfill Eph. 4:12.

According to Paul, pastors—along with other church leaders—are “to prepare God's people for works of service, so that the body of Christ may be built up.”