Why Do We Gather as Christians? (Part One)

True or false: “The New Testament reason for meeting with other Christians is to worship God.”

If you said true, your answer lines up with what most of us have been taught. One website, which suggests how to speak to children about church, begins with: “People go to church to worship God.” We call our main congregational meetings “worship services.” In those meetings we sing “worship songs,” led by “worship leaders” in charge of “worship teams.” Sometimes we call church buildings “worship centers.”

I know it is not RC (religiously correct) to question the nearly universal idea that gathering with other believers is all about worship. So please grant me a little grace as I ask you to examine the evidence for this rarely questioned conviction.

Right off, I’ll reveal my assumed starting-point. I believe Scripture is our only rule for faith and practice. Faith involves what we believe—truths such as the deity of Christ, salvation by grace through faith in Jesus, his bodily resurrection, and so on. Practice involves what we do, including how we meet with other Christians. I am assuming the New Testament, not church traditions, should have the last word on why we assemble.

Check It Out

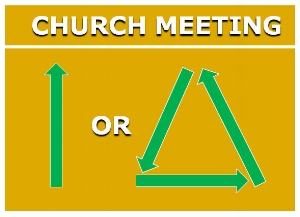

What is “worship”? In the New Testament, the Greek words for worship of God all reflect attitudes and actions directed toward him. Duties carried out toward God. Esteem and reverence directed toward him. Obedience and service oriented toward God. Bowing down toward God. In short, in worship, we aim our attention in a God-ward direction. Think of a single arrow pointing upward from us to God.

If you have a complete concordance, trace the uses of “worship/worshiped/worshiping” in the New Testament. You’ll find that, together, those English words appear about 70 times (NIV version). Yet you will not find those words used in contexts that speak about what we Christians do in our regular gatherings.

Yes, in Acts 13:2, while fasting and praying, a group of prophets and teachers were “worshiping.” Not so much a church gathering as a prayer meeting among church leaders. And in I Cor. 14:25, Paul says an unbeliever, after hearing gathered Christians prophesy, might be led to “worship” God. Here, an unbeliever—not believers—is worshiping. Neither text describes what typically goes on in church meetings. But this is about as close as the New Testament comes in connecting the word “worship” with Christian assemblies.

By contrast, a great many verses describe worship as taking place not in church gatherings but by individuals in other settings. The Magi, upon seeing baby Jesus, worshiped (Matt. 2:11-12). Anna, presumably by herself in the Temple, worshiped (Lk. 2:37). The disciples worshiped Jesus in a boat (Matt. 14:33). As they hurried away from his empty tomb, the two Marys worshiped Jesus (Matt. 28:>9). The man born blind worshiped Jesus (Jn. 9:38). And so on. These are not what we call “corporate worship” occasions.

Others Agree

After a study of all the Greek words translated as “worship” in the New Testament, the late I. Howard Marshall (well-respected as a New Testament scholar) says: “It is a mistake to regard the main or indeed the only purpose of Christian meetings as being the worship of God.” (See "How Far Did the Early Christians Worship God?")

And in Paul’s Idea of Community, Robert Banks writes, “One of the most puzzling features of Paul’s understanding of ekklesia [assembled church] for his contemporaries, whether Jews or Gentiles, must have been his failure to say that a person went to church primarily to ‘worship.’ Not once in all his writings does he suggest that this is the case.”

Then Why Should Christians Gather?

The New Testament leaves no question that we believers should meet. But why? If not to worship, what should be our main purpose for getting together? Think of it this way: you and I are to worship anywhere and everywhere—all alone, with our families, in our workplaces, and in our church gatherings. In other words, worship can rise to God even when no one else is around.

But time after time the New Testament calls us to do something we simply cannot do by ourselves: one-anothering. In his new commandment, Jesus calls us to “love one another” in the way he has loved us (Jn. 13:34). These words became the seed from which the dozens upon dozens of New Testament one-another/each-other instructions grew.

For example, the two one-anothers in Hebrews 10:24-25 explain why we should never stop meeting together: “And let us consider how we may spur one another on toward love and good deeds. Let us not give up meeting together, as some are in the habit of doing, but let us encourage one another—and all the more as you see the Day approaching.” Getting together lets us see and hear each other. This creates the setting in which we may spur on and encourage each other.

This focus on one-anothering when we meet, although in different words, shows up in I Cor. 14:26: “When you come together, everyone has a hymn, or a word of instruction, a revelation, a tongue or an interpretation. All of these must be done for the strengthening of the church.” Each of us has been given one or more gifts to use in building each other up. The New Testament term “fellowship” is a one-anothering word. The church is a body made up of mutually-supportive members. It is a family whose members huddle to help each other. This is shared church.

(Part Two will explore why the single-arrow model does not reflect the gathered-church picture seen in the New Testament. It will also ask, “Why Does Our Purpose for Gathering Matter?”)