Some Inconvenient Church Questions

Several authors have urged a return to what I call “shared church.” But their books don’t appear on best-seller lists, and few Christ-followers know about them. This blog is the seventh on such books.

Milt Rodriguez has a way of asking inconvenient questions about the way we do church. No, he is not anti-church. His slim, 142-page book, The Priesthood of All Believers, makes it clear that he dearly loves the church. But his questions are inconvenient, because they require us either to face them honestly or duck them completely. In his Preface, he lobs the first question:

“Why does the church we see today look so different from the church we see in the New Testament?”

Rodriquez does not think God has any one-size-fits-all blueprint for the church. However, “God does have a pattern for the church. He does care about how the church is built. This ‘pattern’ is based on life, divine life, not rigid organizational machinery.” Just as DNA provides the pattern for our physical bodies, God’s own life supplies the pattern for the Body of Christ.

Rodriguez warns against trying to merely copy the outward actions and forms of the first-century church. Back then, God’s “life flowed out of the people and it took the form of certain actions. Let’s not make the mistake of duplicating those actions in hopes of having the life. That’s backwards. . . . Please do not read this book as a manual on how to do church. These ‘observations’ are simply things I have seen of the pattern of divine life as revealed in the scriptures and in my own experiences.”

“What is the main purpose for us to gather together as believers?”

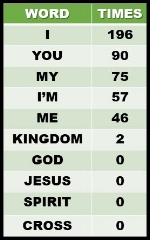

Ask almost any Christian today, and they will say we meet to “worship.” We have worship centers, worship services, worship bands, worship leaders, worship songs, worship seminars, and even worship software. But to this inconvenient question, Rodriguez offers a completely non-traditional—yet biblical—answer. We gather “for the purpose of edification [building up] of the members through their God-given ministry to one another.”

“Even though worship is important, we must realize that worship is not the reason we gather together. Paul teaches that worship is offering up our whole lives to God (see Rom. 12:1, 2). We don’t come together primarily to worship because our whole life is to be an act of worship. We should just continue that flow of worship when we come to meetings.”

This, of course, assumes that our lives through the week have prepared us to have something to offer our fellow Christ-followers. “If we don’t, then we really have nothing to give. . . .Every part or member is to be given freedom to minister as God leads. I Cor. 14:26 makes this very clear.”

“Why does only one person need to bring a teaching?”

Paul told the Roman believers he was convinced that they were “competent to instruct one another” (Rom. 15:14). But Rodriguez observes that “in modern church settings the people just sit there and receive all the time. . . .God wants an activated priesthood. What good is it that we are priests if all we do is sit there and watch like an audience at a show? It’s time for all leaders to train, encourage, and open the way for all the believers to participate in ministry during the meetings.”

He also notes the absence of song or worship leaders in the New Testament churches. Why? “Because all the saints [led] out in songs and sang to God and one another during the meetings.” As Paul puts it in Ephesians 5:19, “. . . speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody with your heart to the Lord.”

“This participatory, every-member-involvement in first-century church gatherings leads Rodriguez to his next inconvenient question:

“Did a church in the first century ever hire one of these [professionals] and pay them a salary to be a ‘Minister’ for their congregation?”

Clearly, the answer is no. As Os Guinness says in his book, The Call: “there is not a single instance in the New Testament of God’s special call to anyone into a paid occupation or into the role of a religious professional.”

Rodriguez agrees: “You will not find anything like our present day clergy system anywhere in the New Testament. It just doesn’t exist. What you find instead is a body of believers who all minister to one another. What you find is a ‘priesthood of all believers.’ . . . Unfortunately, the clergy/laity system has all but destroyed every member functioning within the church.”

Of course, the New Testament church did have leaders. “It was always elders (plural), never elder or pastor (singular).” But, “They are not to be ‘the ministers’ for the congregation. They are not to do all the ministry while the believers sit down and soak it all in. Their ministry is to equip the saints to do their ministry. . . .The elders and deacons were simply priests among priests who were there to train and develop the other believers’ ministries and watch over the church.”

“Where did the professional clergy come from?”

Participatory meetings continued through the first century. The clergy system took root in the second. “At the beginning of the second century there was a man that began pushing for one-man rulership in each church. His name was Ignatius of Antioch. . . .He taught that the bishop had absolute power over the congregation and the elders. The bishop was to perform the Christian ‘sacraments’ of communion, baptisms, marriages, and preach sermons.”

“Cyprian of Carthage came along in the third century. . . .He was responsible for bringing back the Old Testament system of priests, temples, altars, and sacrifices. Bishops now became known as ‘priests’ and were accepted as representatives of God and anyone who questioned them would be opposing God himself.”

Moving on to the fourth century, Rodriguez points out that under the Roman Emperor, Constantine, “the church became more like an organization than a body.” Centuries later, Martin Luther and the Reformation brought the church “a great step forward.” However, “Even though the Bible was put into the hands of the believers, the ministry was not. . . .The priesthood of all believers was not restored to the church. The same clergy/laity system was still used. . . . Instead of being called priests, bishops, cardinals, and popes; now they were called pastors, ministers, parsons, preachers, and reverends!”

Another outcome of the Reformation: church divisions. “Christianity became a very divided and splintered group. Many new organizations, called denominations, began to come forth, each of them rallying around a certain leader or reformer.”

“Why call in a doctor when the body can heal itself?”

Just as God has built healing capacities into our physical bodies, he has also done so in Christ’s Body. “If all the believers are functioning as priests and ministers, then needs can be met quickly and easily instead of some pastor having to be at six places at one time. . . .The church is a life, not just a meeting.”

In other words, “if meetings function the way they that they are supposed to, then the believers will want to be together outside of the meetings as well. During the meeting, people will learn to care for their brothers and sisters and this will cultivate a love between them that will surely extend outside of the meetings. . . .The power, authority, and character of Christ will be expressed through His church. The fullness of Christ will be made visible!”

“Each one should use whatever gift he has received to serve others, faithfully administering God's grace in its various forms.” (I Pet. 4:10)

________________________________